reorganisation within a short time period.”

to climate change that is on the same scale

as the problem itself”

spirit of openness and participation...”

for the historic challenge ahead.”

Table of Contents

FOREWORD

I By Ann Pettifor

II By Bill McKibben

2 PATHWAYS TO THE GREEN NEW DEAL FOR EUROPE

2.1 Introduction

2.2 Green New Deal for the EU

2.3 A People’s Green New Deal

3 GREEN PUBLIC WORKS

3.1 The Engine of Economic Transformation

3.2 How to Pay For It

3.2.1 The GPW Financial Strategy

3.2.2 Harnessing Public Investment

3.2.3 Green Investment Bonds

3.2.4 Macroprudential Management

3.2.5 Taxation and the GPW

3.3 How to Spend It

3.3.1 Guaranteeing Decent Jobs

3.3.2 Empowering Communities

3.4 Where to Spend It

3.4.1 Housing

3.4.2 Infrastructure

3.4.3 Social, Cultural and Health Services

3.4.4 Cooperatives & Community Projects

3.4.5 Green Horizon 2030

3.4.6 Industry

3.4.7 Agriculture and Rural Communities

4 ENVIRONMENTAL UNION

4.1 Introduction

4.2 Legislating for Emergency

4.2.1 Declaring Climate Emergency

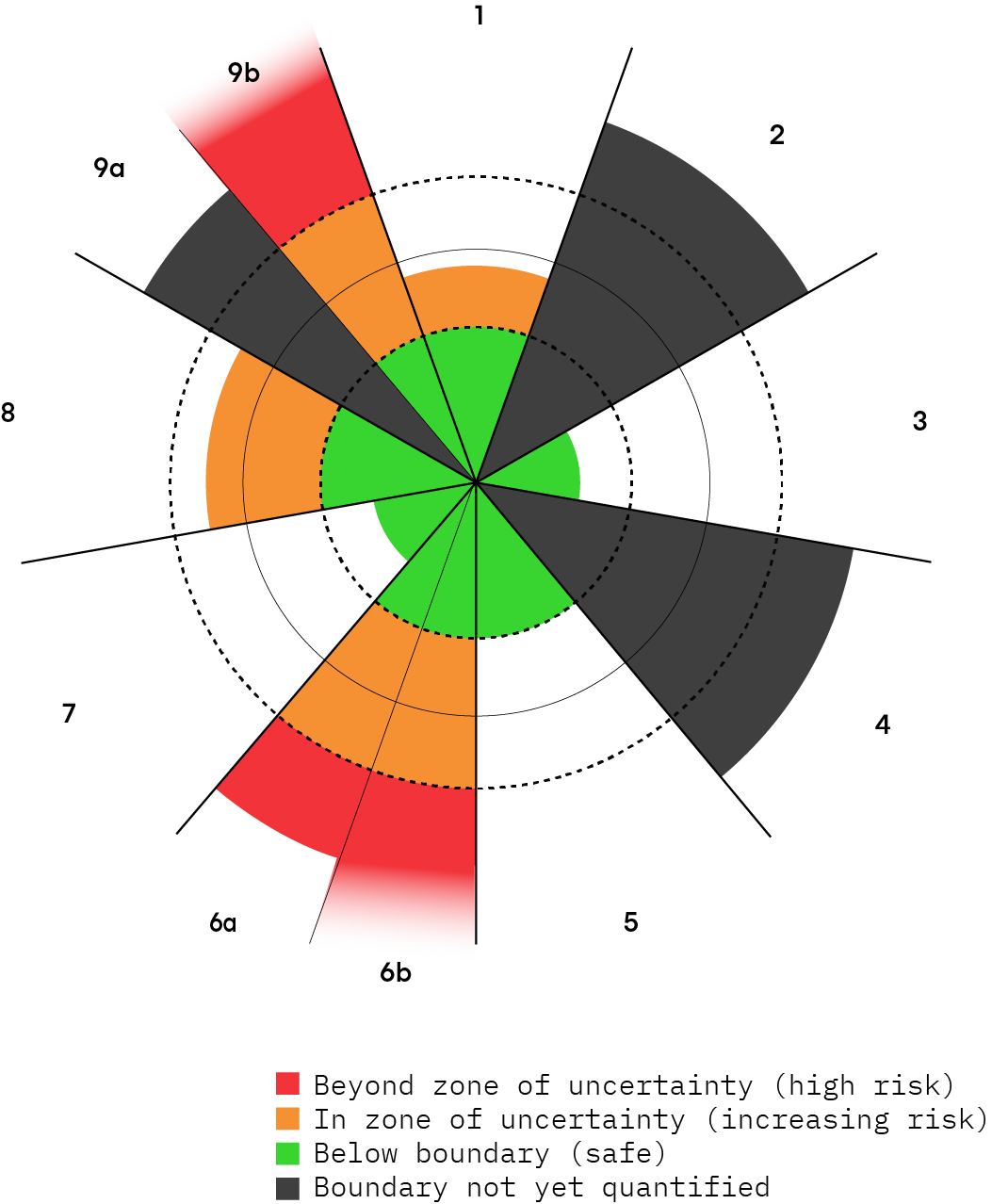

4.2.2 Respecting Planetary Boundaries

4.3 Legislating for Sustainability

4.3.1 Fiscal Interventions

4.3.2 Transport

4.3.3 Energy

4.3.4 Supply Chains

4.3.5 Corporate Finance, Governance and Competition

4.4 Legislating for Solidarity

4.4.1 Agriculture

4.4.2 Trade

4.4.3 Development

4.4.4 The Environmental Abuse Directive

5 ENVIRONMENTAL JUSTICE COMMISSION

5.1 Introduction

5.2 Institutional Design

5.2.1 Principles

5.2.2 Governance

5.2.3 Competencies

5.3 Dimensions of Environmental Justice

5.3.1 International Justice

5.3.2 Intersectional Justice

5.3.3 Intergenerational Justice

Foreword I

By Ann Pettifor

For too long, European environmentalists have treated the ecosystem as almost independent of the international economic system based on deregulated, globalised finance. A system that operates beyond the reach of regulatory democracy, beyond the reach of national and regional borders — and that uses ‘easy’ if costly credit to fuel consumption and production, and to extract assets from the ecosystem. A system operated by unaccountable individuals and corporations. One that acts as if there were no limits to the exploitation of nature and labour.

This report is a blueprint for bringing about an urgent, system-wide reorganisation within a short time period. For society to regain public authority over the international monetary system, to subordinate it to the interests of society and the ecosystem. The Green New Deal for Europe is a giant step in achieving that system change.

We can — and to survive we must — transform the failed system of financialised capitalism that now threatens to collapse earth’s life support systems, and with them, human civilisation. We must replace it with one that respects boundaries and limits; one that nurtures soils and aquifers, rainfall, ice, the pattern of winds and currents, pollinators, biological abundance and diversity. A system that delivers social, political and economic justice.

We know that in the ten years or so that the UN’s scientists believe are left to us, it is possible to achieve such a transformation. One reason change is achievable is this important fact: just 10 percent of the global population is responsible for 50 percent of total emissions. Tackling the consumption and aviation habits of just 10 percent of the global population should help drive down 50 percent of total emissions in a very short time. This understanding helps us grasp the rate and scope of what is possible if we genuinely believe climate breakdown threatens human civilisation and the natural systems on which we depend.

Our confidence should stem from our knowledge of human genius, empathy, ingenuity, collaboration, integrity and courage. Second, from an understanding of our economic system, and in particular of our money and monetary systems. We know that it is possible to transform the globalised financial system and make finance possible for the huge task of protecting the ecosystem, and ending social injustice, because we have done it before — in the relatively recent past.

The Green New Deal is inspired by President Roosevelt’s New Deal because his administration unilaterally dismantled the gold standard — the globalised financial system of his day — and stripped Wall Street of its power to dictate economic policy. Once the elected government was in the driving seat of the economy, and Wall Street was made servant to the interests of the people and of nature, it became possible to resolve the banking crisis of that time; to end the Great Depression; to raise finance and use fiscal policy to create jobs and income and end inequality.

Most importantly, it became possible to address the ecological crisis of that day: the ‘dust bowl’. The administration did so by hiring workers to plant three billion trees, slow soil erosion on 40 million acres of farmland, build 13,000 miles of hiking trails, and develop 800 new state parks.

That is the potential power of the Green New Deal for Europe. It rests on the understanding that finance, the economy and the ecosystem are closely intertwined, and that transformation of the economic system is essential to the transformation of the ecosystem.

With confidence, courage and hope we can tackle climate breakdown, restore biodiversity and save the planet. This report lays down the steps we Europeans must take to achieve that goal.

December 2019

Foreword II

By Bill McKibben

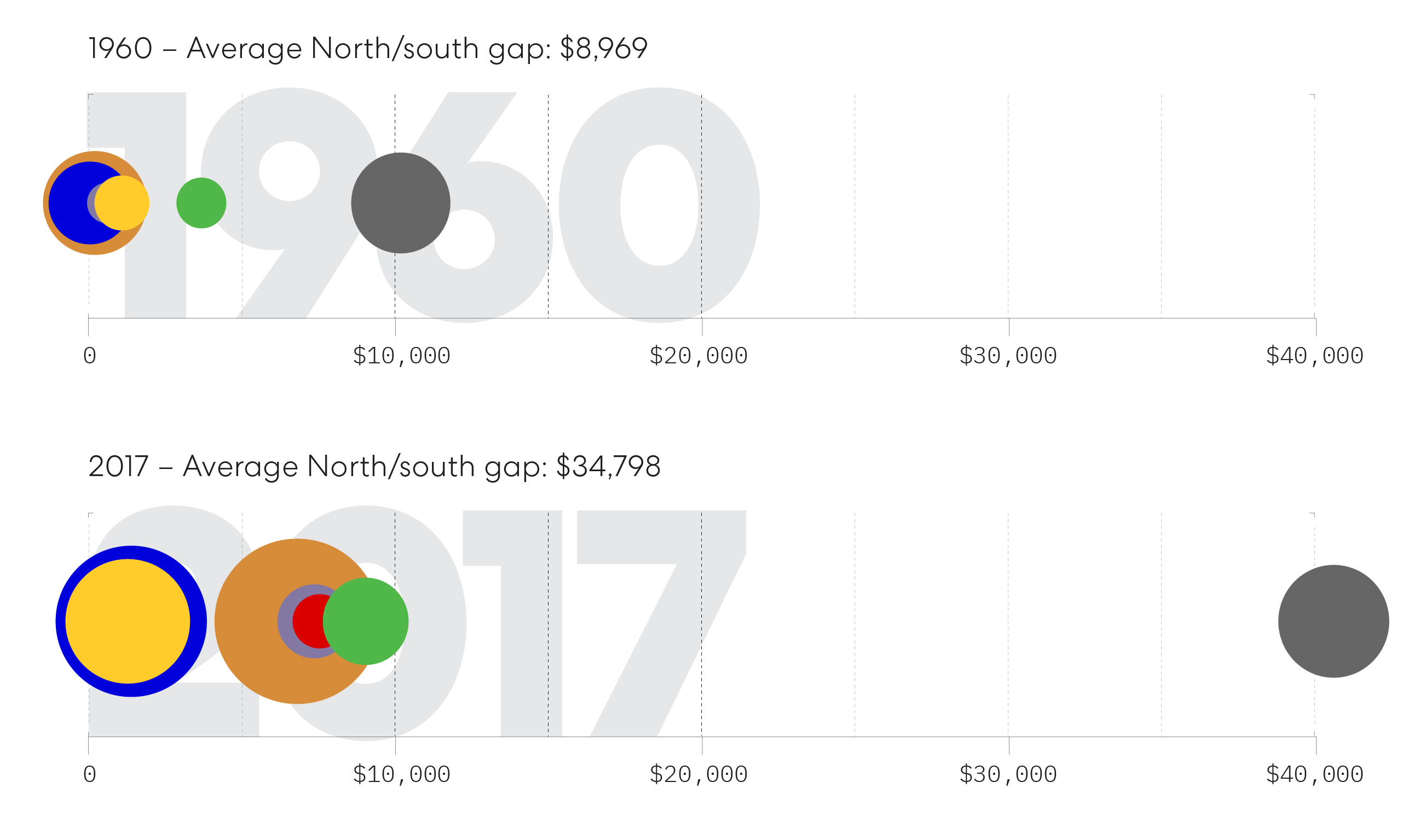

Two particularly baleful trends have begun to dominate life on this planet: the steady destruction of our natural world and the steady rise in inequality.

These are each incredibly dangerous: the climate and environmental crises have us on the brink of a global extinction event on a scale not seen in many millions of years. Inequality is helping destabilize our political life in countries around the globe. These trends are, of course, linked in many ways. Not the least of which is the need for effective and immediate government action to help slow the rising temperature of the earth.

This is why this is such a remarkably important document. The Green New Deal for Europe is the first attempt at a political response to climate change that is on the same scale as the problem itself, and it recognizes that any response to the climate and sustainability crisis must necessarily also deal with the austerity and economic short-sightedness that currently paralyze our societies.

This is by no means impossible — in fact, compared with trying to ride out the status quo it is easy.

The engineers have done their job, dramatically lowering the cost of power from the wind and sun and opening up the prospect of a workable future. Now citizens must do their jobs with the same prowess. We must set the stage for rolling out those new technologies at a pace that actually catches up with the physics of global warming. And we must use the economic opportunity that roll-out represents to reverse the tide of inequality and instead start a trend in the other direction, towards economic justice.

The institutions envisioned in this document will at least get the job started. But one of its crucial postulates is that the response to these crises must be living and dynamic. I am reminded of the original New Deal, a response to the Depression announced by Franklin D. Roosevelt almost a century ago. Under his leadership, a period of intense experimentation tried one solution after another, discarding those that didn’t work and honing those that did. In many cases, these policies deepened social and economic inequalities, between races as between genders. But the original New Deal enshrined the principles of democracy and justice. We must emulate it — and radically improve on it — in that regard.

Roosevelt famously inaugurated the New Deal by saying “there is nothing to fear but fear itself.” We don’t have that assurance, sadly. There is a great deal to fear, on a planet whose icecaps are melting, oceans rising, and cities baking. But there is also a good deal to hope for: above all the human solidarity that can rise above the tawdry exploitation of the last few decades and aim instead for a world that can be both cherished and sustained.

August 2019

Introduction

Europe today confronts three overlapping crises — all of them of its own making.

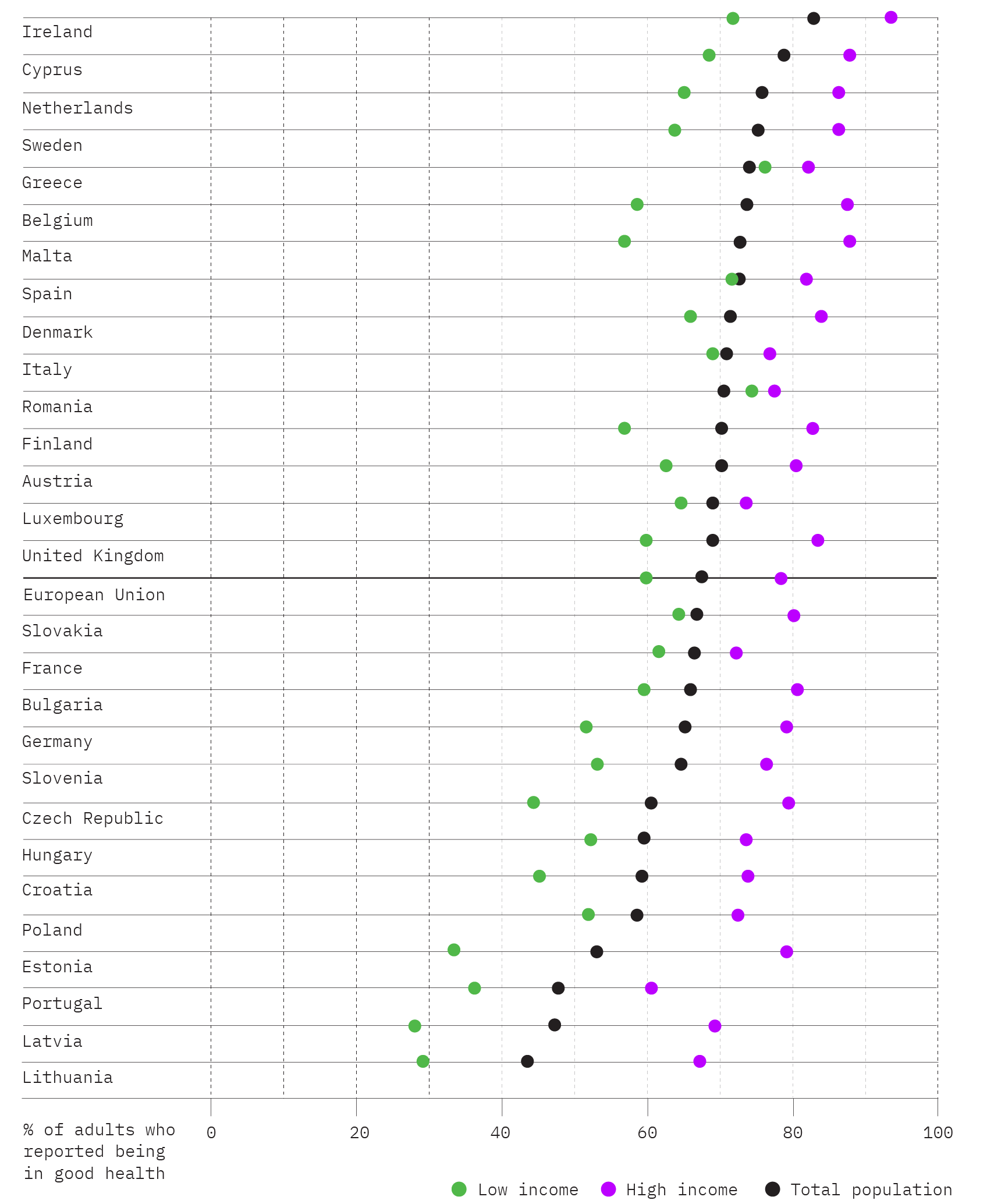

The first crisis is economic. Inequality in Europe is at an all-time high: the top 10 percent of households own half of the continent’s wealth, while the bottom 40 control just three percent.1M. Förster, A.L. Nozal and C. Thévenot, ‘The Social Divide in Europe,’ OECD Centre for Opportunity and Equality, 2017, [link] (accessed 31 July 2019). This is not a story of all boats rising at once. The share of workers living in poverty is on the rise. In 2016, 118 million Europeans, nearly one out of four, were at risk of poverty or social exclusion, with rates of homelessness increasing across the continent.22 Emilio Di Meglio et al. (eds), ‘Living Conditions in Europe’, Eurostat, 2018, [link] (accessed 15 July 2019), p. 26; C. Serme-Morin, ‘Homeless in Europe – Increases in homelessness’, FEANTSA, Report, 2017, [link] (accessed 15 July 2019), p.2. Even in ‘prosperous’ countries like Germany, relative poverty has been steadily rising for the last two decades.3N. Grevenbrock et al, ‘Germany – Selected Issues’, International Monetary Fund, 2017, p.24.

This is a crisis by design. The policy of austerity, which severely constrains the public sector’s spending capacity, has been built into European treaties and reinforced in subsequent agreements. This policy has been particularly devastating for women, children, people with disabilities and communities of colour. And it has starved Europe of investment in public services, worker training, and public infrastructure. Again, even in Germany — just like in France, Spain and Italy — net public investment has recently fallen to below zero.4International Monetary Fund, ‘IMF Fiscal Monitor: Capitalizing on Good Times, April 2018’, IMF Fiscal Monitor, 2018, [link], (accessed 1 August 2019).

The second is a crisis of climate, ecology, and environment. As Bill McKibben notes in the foreword to this report, we are already experiencing a mass extinction: the soil is degrading,5P. Panagos et al., ‘The new assessment of soil loss by water erosion in Europe’, Environmental Science & Policy, vol 54, pp. 438-447. See also ‘Agri-environmental indicator – soil erosion’, Eurostat, November 2018, [link] (accessed 1 August 2019). the earth is heating,6N. Christidis, G. S. Jones and P. A. Stott, ‘Dramatically increasing chance of extremely hot summers since the 2003 European heatwave’, Nature Climate Change, vol 5, 2015, pp. 46–50. the ice is melting, the oceans are acidifying,7IPBES, IPBES Secretariat, Global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science- Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services: 2.2.5.2.1 Ecosystem structure’, Bonn, Germany, 2019 https://www.ipbes.net/global-assessment-report-biodiversity-ecosystem-services (accessed 15 July 2019). and species after species is disappearing from the planet,8Ibid., 2.2.5.2.4, ‘Species populations’. while increasing amounts of greenhouse gases are pumped into our air.9Earth system research laboratory, ‘Trends in atmospheric carbon dioxide’ [link] (accessed 10 July 2019); ‘Trends in atmospheric methane’ [link] (accessed 10 July 2019); ‘NOAA’s Annual Greenhouse Gas Index (An Introduction)’ [link] (accessed 11 July 2019). Large parts of the planet could become uninhabitable within our lifetimes if we do not change our ways, and change them fast.10D. Shindell et al., ‘Quantified, localized health benefits of accelerated carbon dioxide emissions reductions’, Nature Climate Change, 8(4), 2018, p. 291.

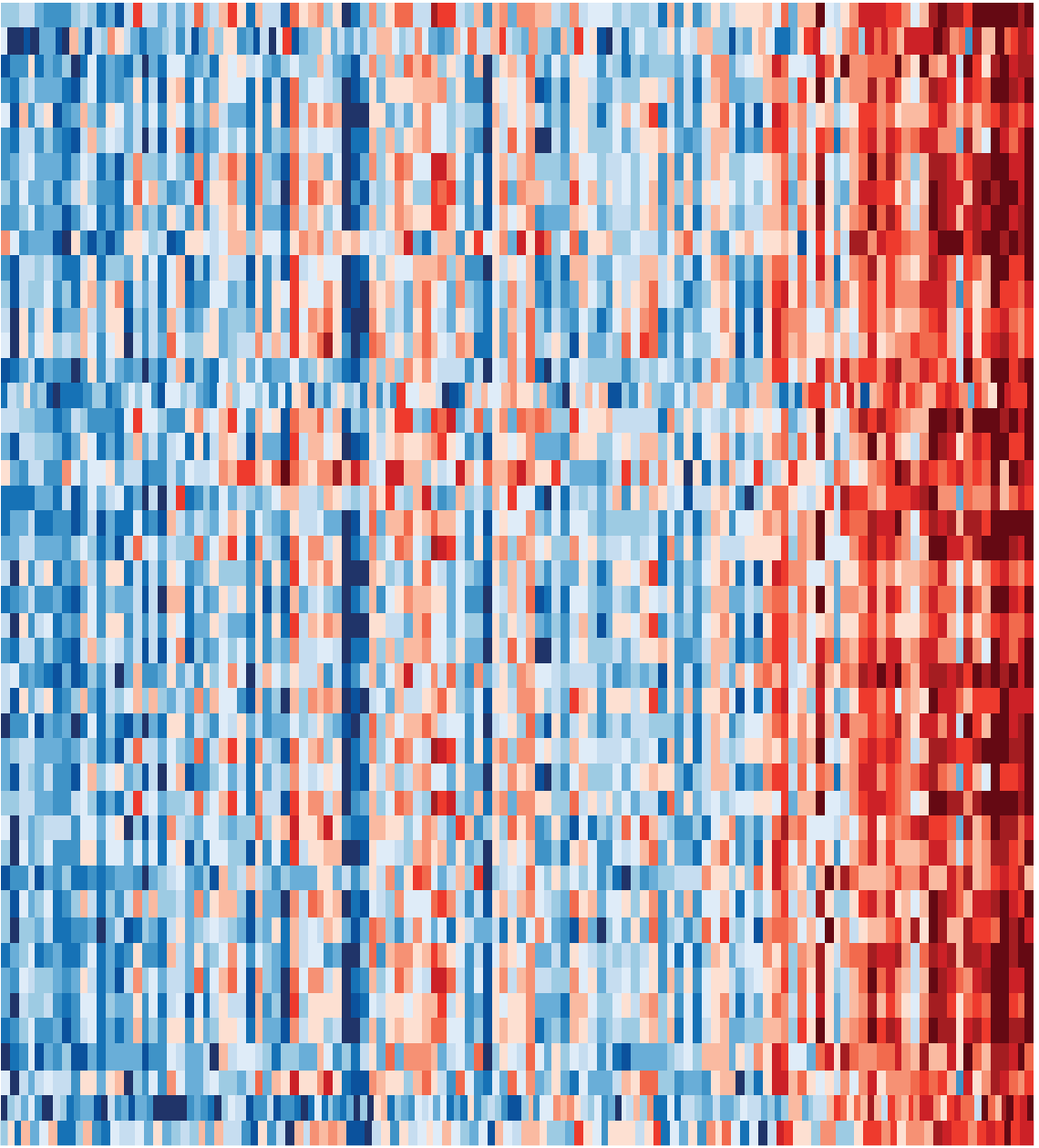

Figure 1

Europe's Warming Stripes

Annual average temperatures for 45 European countries from 1850-2018 using data from UK Met Office.

Source: Ed Hawkins, Berkeley Earth, NOAA, UK Met Office, MeteoSwiss, DWD.

This crisis, too, is a product of our political decisions. Centuries of subsidised pollution — and reckless neglect of the scientific evidence — have wrought havoc not only in Europe, but around the world.11D. Coady et al., ‘How Large Are Global Fossil Fuel Subsidies?’, World Development, vol 91, 2017, pp. 11-27. In all, 75 percent of the terrestrial environment has been “severely altered” by human actions,12IPBES 2019. ushering in a new geological era marked by humanity’s imprint on our lived environment.

The third crisis, then, is a crisis of democracy. Across Europe, people report a profound sense of distrust in political institutions — according to Eurobarometer, only 42 per cent of people trust the EU; only 34 trust their national government13Directorate-General for Communication, European Commission. Standard Eurobarometer 89, “Public opinion in the European Union,” March 2018.— and a sense of disenfranchisement in their economic lives. The institutions of the European Union, in particular, continue to prize the wisdom of technical managers over the needs of the communities that comprise its Union. The voices of front-line communities, bearing the brunt of environmental breakdown, are rarely heard in Brussels.

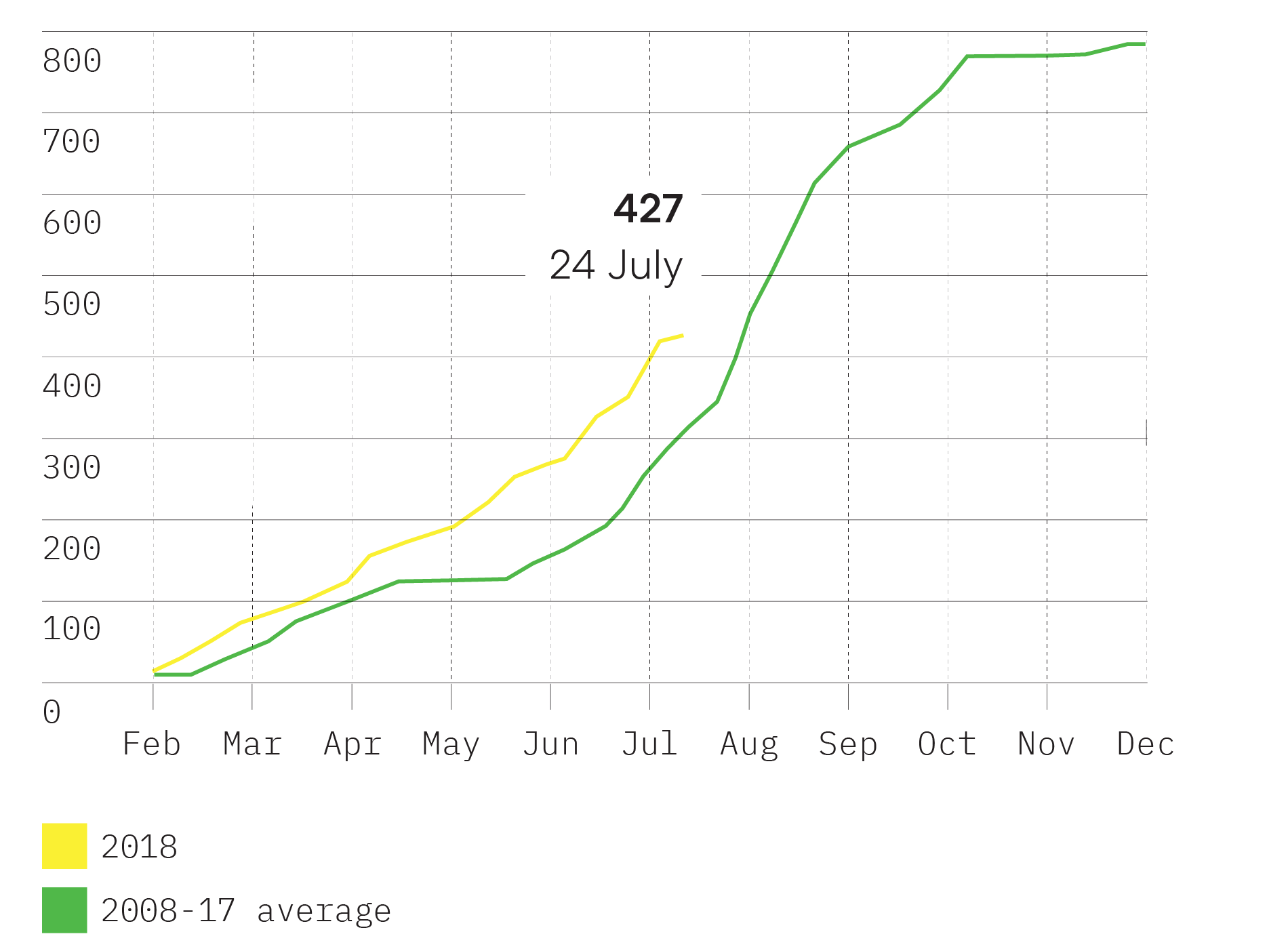

These crises are bound together. The attachment to the failed, growth-oriented economic policies of the past has prevented Europe’s governments from taking necessary action to redress the climate crisis. The result is commonly known as Black Zero: a fanatic pursuit of ‘balanced budgets’ has precluded government action on scientific evidence — even as historic heatwaves blanket Europe,14A. Freedman, ‘A Giant ‘Heat Dome’ Over Europe Is Smashing Temperature Records, And It’s on The Move’, Science Alert, 25 July 2019, [link], (accessed 25 July 2019). disastrous wildfires tear through its towns and cities,15G. Trompiz and J. Faus, ‘Wildfires and power cuts plague Europeans as heatwave breaks records’, Reuters, 29 June 2019, [link], (accessed 10 July 2019). severe droughts strain its harvests,16C. Harris, ‘Heat, hardship and horrible harvests: Europe’s drought explained’, Euronews, 12 August 2018, [link], (accessed 15 July 2019). and scores of people spill into the streets to demand that Europe’s legislators respond to the crisis at hand.

Inequality is also linked to the changing climate in a more direct way. The richest 10 percent of people are responsible for 49 percent of all lifestyle consumption emissions — a measure of what we emit in our daily lives. Their average carbon footprints are 60 times higher than those of the poorest 10 percent.17‘Extreme carbon inequality – Why the Paris climate deal must put the poorest, lowest emitting and most vulnerable people first’, Oxfam Media Briefing, 2 December 2015, [link], (accessed 4 August 2019), p. 4. At the same time, just 100 companies are responsible for 71 percent of all global emissions.18P. Griffin, ‘The Carbon Majors Database – CDP Carbon Majors Report 2017’, CDP Report, July 2017, available at: [link], (accessed 4 August 2019). The aggressive lobbying tactics employed by these companies to persuade European legislators to their cause – over €250 million in Big Oil and Gas lobbying since 2010 alone19Corporate Europe Observatory. “Big Oil and Gas spent over 250 million euros lobbying the EU,” 23 October 2019.— illustrate the close connection between Europe’s three overlapping crises.

A movement is growing to secure a better future. In cities across the continent, students are striking to demand radical action to end the environmental crisis. Their activism has been infectious. Today, in large parts of Europe, voters consider the climate and environmental crises their top priority.20Euronews, ‘Environment is top priority for EU voters, survey suggests’, Euronews, 29 April 2019, [link] (accessed 10 July 2019).

Europe’s political establishment has strived to appear sympathetic to the striking students, and to move swiftly to address their concerns. European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen has pledged to deliver a ‘green deal,’ with a commitment to make Europe “the world’s first climate-neutral continent.” “I want the European Green deal become Europe’s hallmark,” she said in September.

But the content of this ‘green deal’ is woefully inadequate to the challenge at hand. In size and speed, scale and scope, the plan fails to respect the scientific consensus about the demands of a just transition. And it leaves intact the basic economic architecture in the EU that has created the social and ecological crises we face today, one centred on growth and profit rather than people and planet. By the standards set out in our campaign’s 10 Pillars21D. Adler and P. Wargan, ‘10 Pillars of the Green New Deal for Europe’, Green New Deal for Europe, 2019, [link], (accessed 8 November 2019).publication, then, Ursula von der Leyen’s ‘green deal’ does not qualify as a Green New Deal.

This report — an updated version of the first edition sent out for public consultation in September 2019 — is therefore the most comprehensive vision of a Green New Deal for Europe. It has benefitted from the expertise, oversight, and creativity of hundreds of activists, scientists, and policymakers who have helped transform this Blueprint into a visionary document to set the course for the green agenda in Europe.

That agenda is composed of three major initiatives. The first is the Green Public Works: an investment programme to kickstart Europe’s equitable green transition. The second is an EU Environmental Union: a regulatory and legal framework to ensure that the European economy transitions quickly and fairly, without transferring carbon costs onto front-line communities. The third and final is an Environmental Justice Commission: an independent body to research and investigate new standards of ‘environmental justice’ across Europe and among the multinationals operating outside its borders.

Our Blueprint offers European leaders, activists and communities a comprehensive — and realistic — plan for Europe to meet the scale of the historic challenge ahead. Calibrated in the right way and implemented with urgency, the policies proposed in our paper could see Europe reach net-zero CO2 emissions by 2025 — a target that is consistent with the principle of equity as embodied in the “common but differentiated responsibility” clause in the Paris framework. Given Europe’s greater responsibility for historical emissions, and greater technological and financial capacity, it must lead the way.

But, to succeed, the policies proposed in this paper cannot be implemented piecemeal. Their implementation must be grounded in coordination across sectors — from agriculture and urban planning to water use and industry — to facilitate a deeper understanding of the interconnected forces driving climate and environmental breakdown.

These policies must be brought to life in Roosevelt’s spirit of ‘bold, persistent experimentation’. “It is common sense to take a method and try it. If it fails, admit it frankly and try another,” Roosevelt said. “But above all, try something.”22Roosevelt Institute, “Bold, Persistent Experimentation vs. Bold Persistence”, Roosevelt Institute, 6 May 2011, [link], accessed on 21 October 2019. This means, first of all, breaking with a status quo sustained by the rehabilitation of failed solutions.

It is not enough, then, to propose an agenda and expect the leaders of the EU to heed its wisdom. That is why our Blueprint includes a chapter on ‘Pathways to the Green New Deal,’ showing how people’s assemblies — democratically elected, locally organised — can drive this vision to reality. We cannot afford to wait around: we can begin to build the just transition today. This report aims to show how.

Pathways to the Green New Deal

A plan to bring the Green New Deal to communities around Europe.

Introduction

Developed by a coalition of activists, economists, scientists, and trade unionists, this Blueprint offers a comprehensive policy vision of a just transition in Europe. But the work cannot stop there: A policy vision is meaningless in the absence of a strategy to realise it. “The Green New Deal cannot just be a campaign,” write Fatima Zahra-Ibrahim and Hannah Martin. “It has to be a social movement.”23F. Zahra-Ibrahim and H. Martin, ‘Green New Deal Politics: From Grassroots to Mainstream’, Common Wealth Green New Deal report series, 27 August 2019, [link], (accessed 8 November 2019).

This chapter — an addition to the first edition of the Blueprint — sets out the pathways to the Green New Deal for Europe that start from the grassroots and end in policy implementation.

The chapter charts two pathways, in particular.

The first, a Green New Deal for the European Union, makes the case that a transnational movement, built around the concerns of front-line communities across the continent, can confront the EU and insert its demands at the heart of the so-called ‘European Green Deal,’ filling the democratic deficit at the heart of the EU.

The second, a People’s Green New Deal for Europe, starts from the premise that the EU has proven to be an unreliable — if not hostile — steward of the environmental justice agenda, and sets out a plan to organise People’s Assemblies at municipal, regional, national, and European levels to deliberate and deliver the policies set out in this Blueprint.

Anti-systemic movements have long struggled to articulate a strategic direction. Is the goal to capture the current system to deliver the just transition? Or is it to dismantle the system and replace it with one that will? The premise of this chapter is that these pathways are not mutually exclusive. No social movement for a Green New Deal can afford to ignore the EU as a set of powerful coordinating institutions and the locus of continental political mobilisation capable of responding at scale to the immediacy of the challenge ahead. Indeed, the Commission’s ‘Green Deal’ provides a clear target for activists to mobilise around.

Equally, no social movement for a Green New Deal can dispense with People’s Assemblies as an essential tool to ensure that our green transition is grounded in democratic principles — and does not fall into the trap of President Emmanuel Macron’s fuel tax legislation, which pit community needs against the green agenda. It is only by pursuing both pathways — simultaneously — that we can realize the full scope of this policy vision.

Green New Deal for the EU

The primary purpose of a Blueprint for Europe’s Just Transition is to translate the transformative ambitions of the Green New Deal into a policy package for the EU. It targets the EU for three primary reasons. First, because the EU has an historical obligation to drive the global green transition. Second, because the EU has the necessary institutions and policy instruments to do so. And third, because the EU continues to suffer a dangerous crisis of legitimacy, which can only be resolved by addressing Europeans’ climate concerns and raising their standards of living — by delivering, in other words, a Green New Deal for Europe.

The publication of this Blueprint coincides with a unique opportunity to push the Green New Deal agenda in the EU. The European Parliament elections of May 2019 saw a ‘green wave’ crash over Europe, as millions of young voters raised their voices to demand swift action to end the environmental crisis. With students striking all across the continent, Ursula von der Leyen committed the European Commission to deliver a ‘European Green Deal’ within its first 100 days, pledging to make Europe into the first carbon-neutral continent in the world.

Commentators have hailed the EU’s ‘Green Deal’ as a visionary policy, promising to unlock billions of euros in ‘sustainable’ investments, implement fresh regulations to curb carbon emissions, ramp up Europe’s climate targets, and do more to protect biodiversity across the continent.

But while the European Commission has made a clear step forward in its rhetorical commitment to a “just transition for all,” the policies themselves lack the strength, ambition and credibility to deliver it. Indeed, von der Leyen’s choice of words is telling. Rather than associate with the tradition of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, she neatly excised the word ‘new’ from her ‘green deal.’ And through this careful omission, a radical vision of economic, social, and environmental justice is transformed into familiar Brussels-speak — and a strategy to sustain its status quo.

As outlined in the 10 Pillars of the Green New Deal for Europe — and, indeed, as emphasised in the preamble to the 2015 Paris Agreement24Paris Agreement, (adopted 12 December 2015, entered into force 4 November 2016), United Nations Treaty Collection, [link], (accessed 9 November 2019).— democracy is a fundamental component of the environmental justice agenda. “Europe’s green transition will not be top-down. It must empower citizens and their communities to make the decisions that shape their future.”25D. Adler and P. Wargan.

But von der Leyen’s ‘Green Deal’ only serves to deepen the democratic deficit at the heart of the EU. The so-called ‘Sustainable Europe Investment Plan’ does not provide resources for communities, municipalities, or regions to invest in their housing or utilities. Instead, it subsidises private investors, socialising the risks of the green transition while privatising the gains. Those who live in Europe are given no control over the direction of Europe’s decarbonisation.

Across the continent, millions do not recognize themselves in the climate movement. Indeed, in fossil fuel-dependent countries like Poland and Hungary, climate change can appear less of a threat than the proposals for addressing it. The EU’s current proposal for a ‘Green Deal’ explains why. By approaching the environmental crisis from the top-down, the EU has failed to show these communities how the green transition will benefit them — by building better housing, securing better jobs, ensuring greater control over their lives. And in doing so, it has sown the seeds of its own failure.

Von der Leyen’s proposal nonetheless represents a victory for the climate movement — and an opportunity to turn up the heat on Europe’s institutions. On both sides of the Atlantic, radical activism put the idea of a Green New Deal firmly on the political agenda. This must be seen as a precedent and a signal that the political goalposts are ours to move.

The pathway to a Green New Deal for the EU, therefore, starts with Europe’s communities.

The first step is to bring the Green New Deal for Europe into communities across EU member states, weaving their core concerns into the definition of environmental justice. For some, justice entails addressing youth unemployment. For others, it entails the provision of better heating in the winter. Decarbonisation, as a mass political project, has the capacity to address both of these concerns — and mobilise the communities that express them.

The second step is to bring these communities together around a shared vision for the EU. The climate debate in Europe is often framed as a zero-sum exchange: Southern countries are pitted against Northern ones; borrowers against lenders; ‘clean’ economies against coal-dependent ones. The Green New Deal for Europe begins from the premise that the green transition can be positive-sum, and the policies we set out in this Blueprint illustrate this logic clearly. Essential to the pathway to a Green New Deal for the EU is powering a transnational movement that can — despite its disparate concerns — stand together behind a single policy vision.

The third and final step, then, is to bring this movement to Europe’s institutions. The democratic deficit of the EU is not only a product of institutional design; it is also because the EU is physically isolated from the democratic pressures that rise up in cities and regions across Europe. The challenge of a pan-European movement for a Green New Deal resides here, in channeling the energies of activists across the continent to clash with the institutions that sit at the Belgian capital — through strikes and sit-ins, occupations and demonstrations: the full arsenal of direct action and civil disobedience.

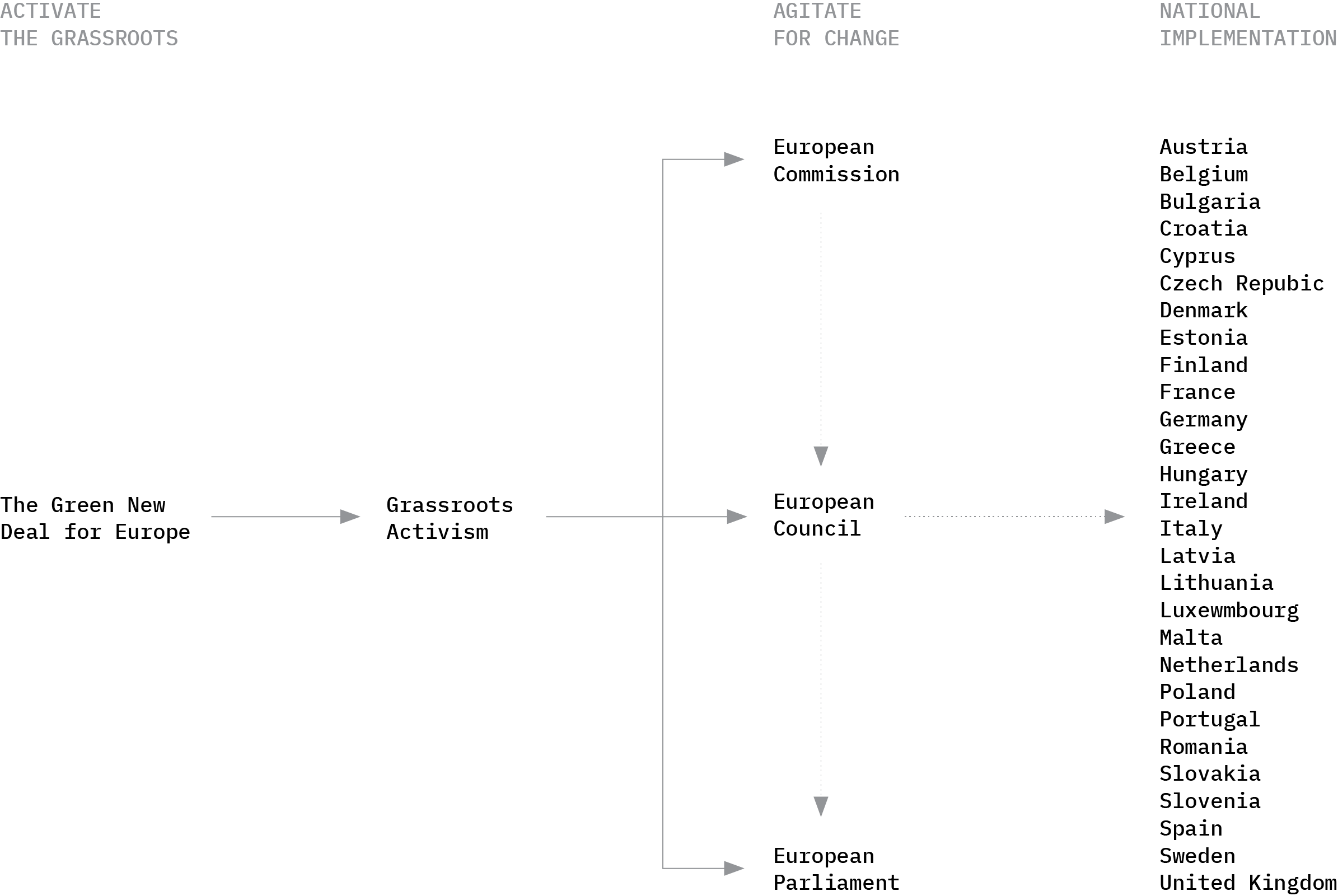

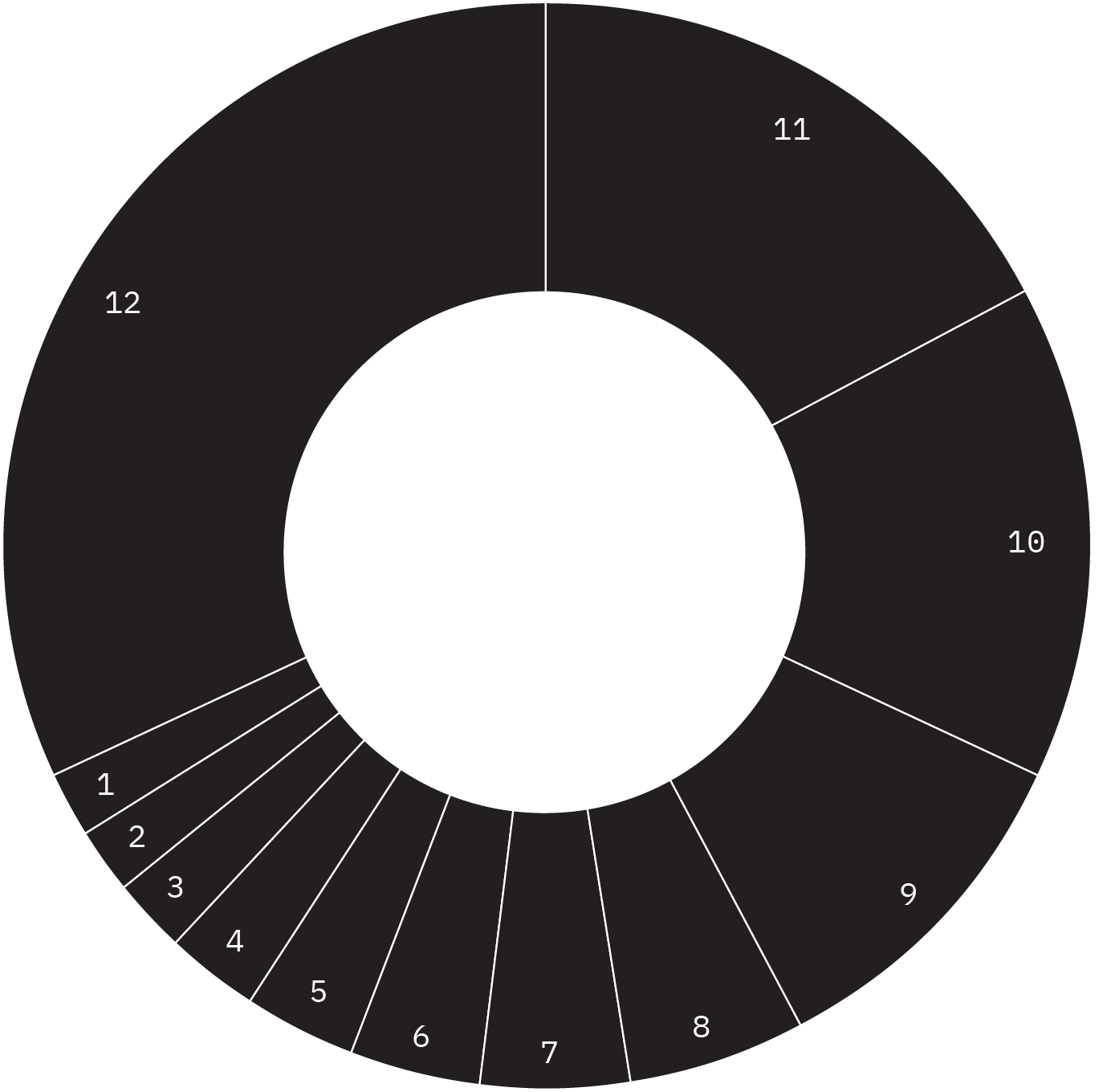

Figure 2

A Green New Deal for the EU

A strategy for mobilising activists around Europe to push Europe's institutions to adopt more radical policies.

But if the Green New Deal for the EU offers a pathway to civic action in Brussels, it must also aim to mobilise European lawmakers in their own communities and EU member states across the continent. Activists around Europe can work together to bring common demands to MEPs and Commissioners in their countries of origin — in addition to targeting those national officials who negotiate the Commission’s legislative proposals at the European Council. In other words, local action, coordinated transnationally, can target every level of the EU’s legislative process. Similarly, national-level lawsuits on areas ranging from environmental justice to social rights can build up a body of European case law — setting precedents and building momentum for further action.

This is a logic of confrontation, pitting Europe’s communities against the European institutions that seem unwilling to see the climate and environmental crisis through the lens of their lived realities — and bringing on board allies inside those institutions who can champion this agenda on their behalf.

The other necessary pathway to a Green New Deal for the EU is through the logic of institutionalisation. Just as anti-systemic movements have historically struggled to articulate clear political demands, they have also failed to formulate institutional strategies to make them a reality. The climate and environmental agenda presents a unique political opportunity: public concerns are increasingly aligned with the demands of the grassroots, creating an electoral force that could power political campaigns. A key task for activists, then, is to identify and support electoral expressions of their agendas — to transform the EU from within.

There are very good reasons for the EU to take up the challenge. The crisis of legitimacy in the EU remains acute, and the fragmentation of European politics will likely cause the EU institutions to seize up and stop working — deepening that crisis further still. The only way out of the rut is to table legislation that tackles the twin crises of environment and economy, and in doing so, revives public faith in the European project.

The clock is ticking: the first 100 days of the von der Leyen Commission begin to count down from December 1. If there were ever a time to band together to demand radical action on the EU, it is now. This is a crisis we cannot afford to waste.

Recommended Action: Inject democracy into the European ‘Green Deal’ by employing the full arsenal of civil disobedience at Brussels — including an urgent public mobilisation during the Commission’s first 100 days.

Recommended Action: Organise a transnational grassroots coalition to agitate, lobby, and petition EU officials both in Brussels and across EU member states, building pressure around core demands of the Green New Deal for Europe.

Recommended Action: Build a pan-European legal team to challenge legislation and coordinate legal action on behalf of a common agenda of climate, environmental and social justice.

A People’s Green New Deal

But our eyes must be open. Time and again, the institutional managers of the EU have proven unwilling to recognise the scale and the urgency of the climate and environmental crisis. On the contrary, policies like the European Central Bank’s quantitative easing (QE) programme — introduced under the auspices of economic recovery — have actively encouraged environmental destruction.26See Sini Matikainen et al., “The climate impact of quantitative easing,” Policy Paper, Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment, May 2017.

The rapid adoption of a ‘Green Deal’ inside the EU — and the appearance of buzzwords like ‘circular economy’ and ‘farm to fork’ in the guiding vision of Commission President Ursula von der Leyen — are positive signs. But no social movement can stand on the quicksand of political caprice: the Green New Deal must build its own infrastructure to organise communities and build consensus among them. This strategy is more than a contingency plan; it is an essential ingredient of environmental justice.

That is why we are proposing to form People’s Assemblies for Environmental Justice as the second pathway to a Green New Deal for Europe.

A People’s Assembly is a form of direct and deliberative democracy that brings citizens and residents of all backgrounds to formulate solutions to shared challenges. The climate movement today — whether it takes the form of student strikes, Extinction Rebellion, or the Gilet Jaunes — has articulated a shared enemy: climate and environmental breakdown. But it has yet to come together to articulate a set of shared demands.

This Blueprint provides a general framework for Europe’s just transition, but it must be complemented by deliberation at the ground level to decide where the resources raised by the Green Public Works programme will be directed. No campaign, movement, union, NGO, or political party can devise a climate plan on its own; the People’s Assemblies for Environmental Justice offer a common process by which to develop it.

Los Indignados – A Blueprint for Activating the Grassroots

In 2011, a series of demonstrations broke out around Spain. Organised by Democracia Real Ya (Real Democracy Now), the protests took aim at the economic crisis that had engulfed the country. They quickly morphed into a movement.

The los indignados movement began to organise weekly occupations of public spaces in Spain. There, it hosted public assemblies, discussing ideas for change and making decisions collectively. Everyone was invited to speak and to vote. No one held a veto.

This culture of civic participation birthed new economic models.

One assembly in Madrid organised an informal market on which community members could exchange services for free. A Catalan cooperative pooled together debtors to give them leverage in dealing with creditors. Another assembly supported people in precarious employment or those who were unable to pay their rents.

By connecting communities around shared concerns, the los indignados movement won the support of Spaniards across the political spectrum — and paved the way for greater community involvement in local decision making.27G. Blakeley, ‘Los Indignados: a movement that is here to stay’, openDemocracy, 5 October 2012, [link], (accessed 7 November 2019).

The People’s Assemblies do not have to be formally sanctioned by political institutions. On the contrary, they can be self-organising. An advisory board, composed of local residents, facilitates sortition of the assemblies and ensures that all material presented to the Assembly is appropriately balanced. Coordinators, with the help of this advisory board, then form a panel of experts to assist Assembly members, who — as in the case of Ireland’s Citizen Assembly — define relevant questions they would like answered by the panel. Finally, an oversight panel of residents, representatives of local government, and relevant community organisations monitor the process and ensure the Assembly arrives to its goals.

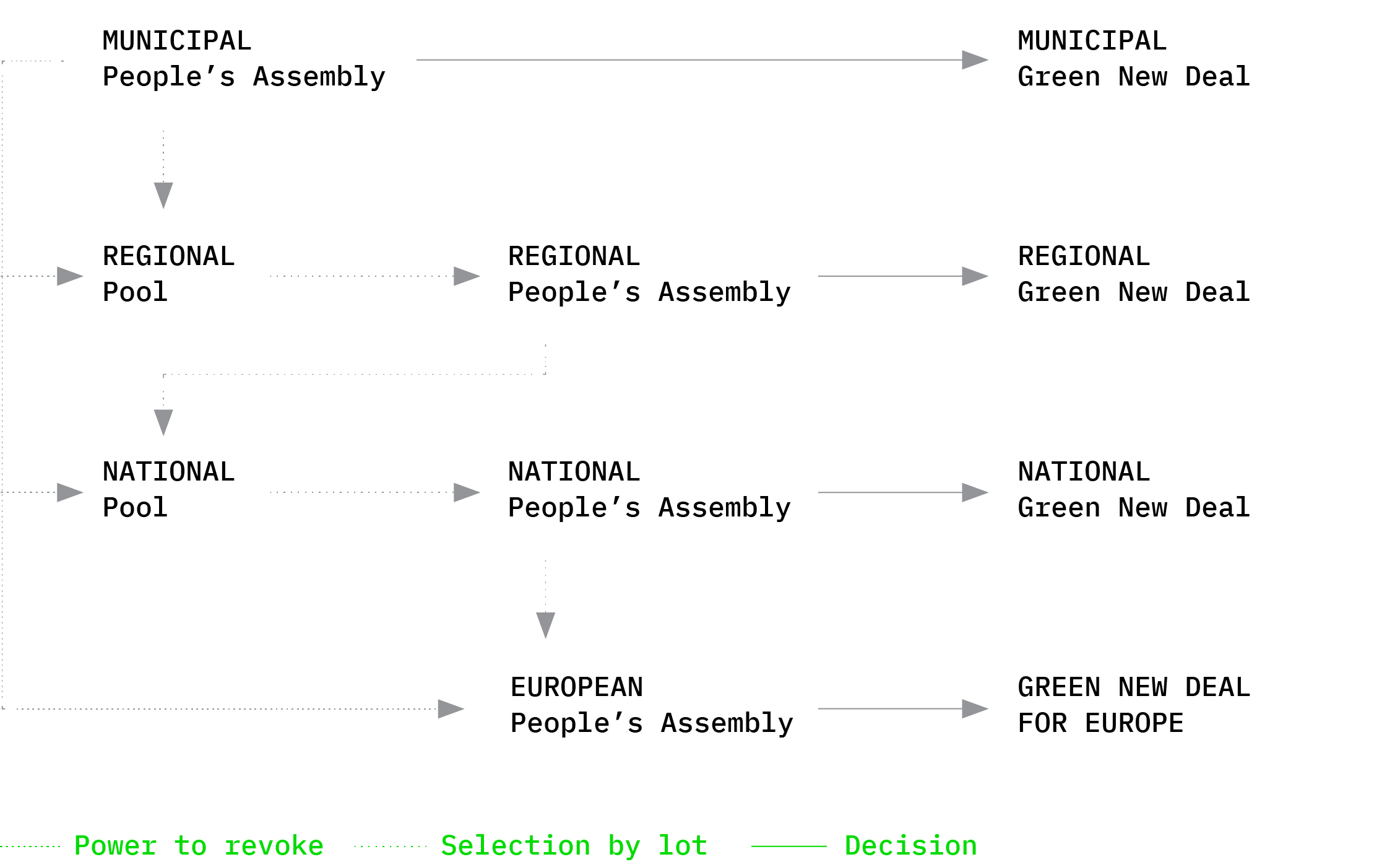

The Green New Deal for Europe proposes to form People’s Assemblies at every level: municipal, regional, national and up to the European. Figure 3 sets out the process: self-organised municipal assemblies are the smallest core unit, which feed through into regional reserves that — through sorition — form regional assemblies, and upward. Each level is responsible for developing its own set of priorities and policy recommendations — a Green New Social Contract — that can form the basis for negotiations with relevant representatives.

Figure 3

A People’s Green New Deal

Mobilising Europe’s communities to drive the just transition.

This process should begin where power is closest at hand. Across Europe, a movement for ‘radical municipalism’ is rising, capturing seats on city councils and — in cases like Barcelona, Palermo, and Amsterdam — taking over municipal government entirely. The People’s Assembly strategy should begin with areas with strong municipalist traditions, not only because they are the most likely to participate in self-organised assemblies, but also because these areas can pilot a new relationship with local government, relying on and taking inspiration from the People’s Assemblies for Environmental Justice.

The case for local action is strong because the EU is the sum of its parts. The implementation of a Green New Deal by a municipality, region or country could serve as a beacon for others, paving the way for radical transformation at the EU level. But to move past the national, local movements must centre internationalism at the core of their demands: the solutions to global warming must be global by design.

People’s Assemblies, then, will catalyse meaningful change at both the local and international level. They will also reproduce a culture of civic participation — engendering norms of public engagement on which the success of many of the proposals set out in this Blueprint depend. The indignados movement in Spain offers us a model for how this can work.

But this process must scale. As Bill McKibben notes in the Foreword, the engineers have done their job, setting us up to address the problem of environmental breakdown at the continental level. “Now citizens must do their jobs with the same prowess,” McKibben writes — and contribute to Europe’s legislative solution by coming together in a continental People’s Assembly. Such a European Assembly would not only give structure, motivation, and purpose to the social movement behind a Green New Deal for Europe. In doing so, it would also help to fill the democratic deficit at the heart of the EU, injecting people’s needs, dreams, and demands into a legislative process that has long presumed to know them better.

Case Study — The People’s Assembly on Climate in Luxembourg

On 19 October 2019, the coalition known as United for Climate organised a People’s Assembly in Luxembourg City. The assembly was supported by a range of NGOs, unions, and social movements, including Extinction Rebellion, Rise for Climate, Youth for Climate and our Green New Deal for Europe campaign.

Preparations for the assembly began with weekly meetings in late summer, with key funding provided by the partner NGOs.

The Assembly was held in a local school. Food was provided by a transition cooperative. On-the-spot child care was also provided to allow parents to take part in the discussions.

The Assembly created a space for various members of the climate movement — from IPCC representatives and the Luxembourg Minister of Environment to members of the local community — to reflect on the climate and environmental crises and the responses to them.

Topics were proposed by the participants. Related topics were combined to form discussion groups. Each group convened for an hour and the minutes of these meetings were immediately distributed to allow all participants to know what was said in other groups.

The same method was used to propose and select topics to discuss the next point of action or demands of the climate movement in Luxembourg. Through this deliberation, a clear set of shared dreams and demands emerged, from a shorter working week to higher-quality public transport systems.

The experience of the People’s Assembly was to organise, fortify, and unite the climate movement in Luxembourg. The challenge is to organise these events over a sustained period of time in order to allow for a comprehensive vision to emerge. This method is not without limits, including — and most important — the restricted participation by working families with existing time commitments.

Nonetheless, the experience of the Luxembourg People’s Assembly — as a self-organised experiment in direct and deliberative democracy — is one that can scale across Europe through the social movement for a Green New Deal.

Recommended Action: Build the movement for a Green New Deal for Europe by mobilising European residents at the local level, through door-knocking campaigns and similar initiatives.

Recommended Action: Organise municipal, regional and national People’s Assemblies for Environmental Justice — uniting experts, activists and scientists in developing a bottom-up vision for Europe’s just transition.

Recommended Action: Scale the People’s Assemblies from the municipal level up to the European one in order to arrive at shared legislative priorities and ground the legislative process in democratic procedure.

Green Public Works

The investment plan to power Europe’s green transition and transform its economy along the way.

The Engine of Economic Transformation

The Green New Deal for Europe is more than a vehicle for redirecting resources to the fight against climate and environmental breakdown. It is a promise to build a fairer and more democratic economy, generating decent jobs, protecting workers’ rights, and empowering communities to shape their futures. This is the vision behind the Green Public Works (GPW), an historic public investment programme powered by the European Investment Bank.

Like Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s Public Works Administration (PWA), founded to oversee government investment during the Great Depression, the GPW programme is Europe’s engine of economic transformation.

But its mandate is broader than that of the PWA. Roosevelt sought to boost industrial output and infrastructure development as a means of economic recovery. The GPW, by contrast, links economic aims with a broader vision of environmental justice: decarbonising Europe’s economy, reversing biodiversity loss and tackling inequalities in Europe and around the world. In other words, the Green New Deal for Europe must not further a destructive ‘green growth’ agenda.

The science shows that it is not feasible to transition to renewable energy quickly enough to stay under 1.5 degrees Celsius if total energy consumption continues to grow.28J. Hickel and G. Kallis, ‘Is Green Growth Possible?’, New Political Economy, 17 April 2019, [link], (accessed 11 July 2019). All scientific models of climate heating assume continued growth in gross domestic product, which is increasingly proving to be incompatible with safe pathways towards a 1.5 degree Celsius world. See also: S. Evans, ‘World can limit global warming to 1.5C ‘without BECCS’’. Carbon Brief, 13 April 2018, [link], (accessed 25 July 2019). At the same time, models indicate that a significant reduction in energy demand can put us on a 1.5 degree pathway without requiring the deployment of dangerous geoengineering solutions.29Grubler et al., ‘A low energy demand scenario for meeting the 1.5 °C target and sustainable development goals without negative emission technologies’, Nature, 2018, [link], (accessed 31 October 2019).

Decarbonising Europe’s economies means more than investing in renewables. It also means scaling down aggregate energy use in order to enable a rapid transformation to an economy that respects planetary boundaries. This must be done in a fair and progressive manner that enhances, rather than restricts, human well-being.

In addition to phasing out Europe’s existing carbon-intensive energy systems and infrastructure, aggregate energy demand must also be reduced by scaling down material production and throughput. The GPW supports this transition by shifting income and welfare creation from industrial production to social and environmental reproduction: maintenance, recycling, repair, and restoration of environmental and infrastructural resources, as well as education, culture and care — for both people and planet.

Beyond reaching net-zero emissions, the Green New Deal for Europe must also work to reverse biodiversity loss, soil degradation, and other forms of environmental breakdown. The reduction in throughput will already release pressure on Europe’s natural systems, but the GPW will do more. It will reinvigorate Europe’s rural communities by investing in small-scale, regenerative farming, forestry and fishing practices — and ending the destructive practices of Europe’s large agribusinesses.

Finally, the GPW is a major jobs programme that not only creates meaningful new jobs, but improves the standards of workers today.

Europe faces increasing inequality and economic concentration. People across the continent live in precarity, which also constrains their ability to live sustainably. Many are worried that environmental measures will add to the pressures they face in their daily lives, whether through job losses or higher living costs. The Green New Deal for Europe will address these concerns and, rather than demanding sacrifice from the vulnerable, offer livelihood security, stability and equality. It will, in other words, be a real solution to the problems faced by communities who are struggling to make ends meet.

This section will set out how we pay for the GPW, how the programme could work and what it will do for Europe’s communities.

1 Policy Recommendation: Establish the Green Public Works, a public investment agency that will channel Europe’s resources into green transition projects around the continent.

How to Pay For It

The scale of the present crisis is clear. Scientific projections show that even small increases in global temperatures will generate massive costs — for humans, for nature and for our balance sheets.

Yet many proposals advanced to address the climate and environmental emergencies continue with Europe’s ‘business as usual’. They refuse to challenge the constraints of fiscal austerity.30

See, for example, U. von der Leyen, ‘A Union that strives for more – My agenda for Europe’, 2019, [link], (accessed 4 August 2019).

They rely heavily on corporate incentives and behavioural nudges. And in doing so, they promise to provide a fraction of the resources that will be necessary to avoid costly environmental collapse.

The Green New Deal proceeds from the premise that the European Union (EU) can and must use all the tools in its arsenal to initiate a swift and just ecological transition. Among these tools, public financing has both the strongest firepower and the clearest path toward immediate execution. The EU has ample resources to put to use in the GPW programme. And it is clear that a new approach to deploying these resources is needed.

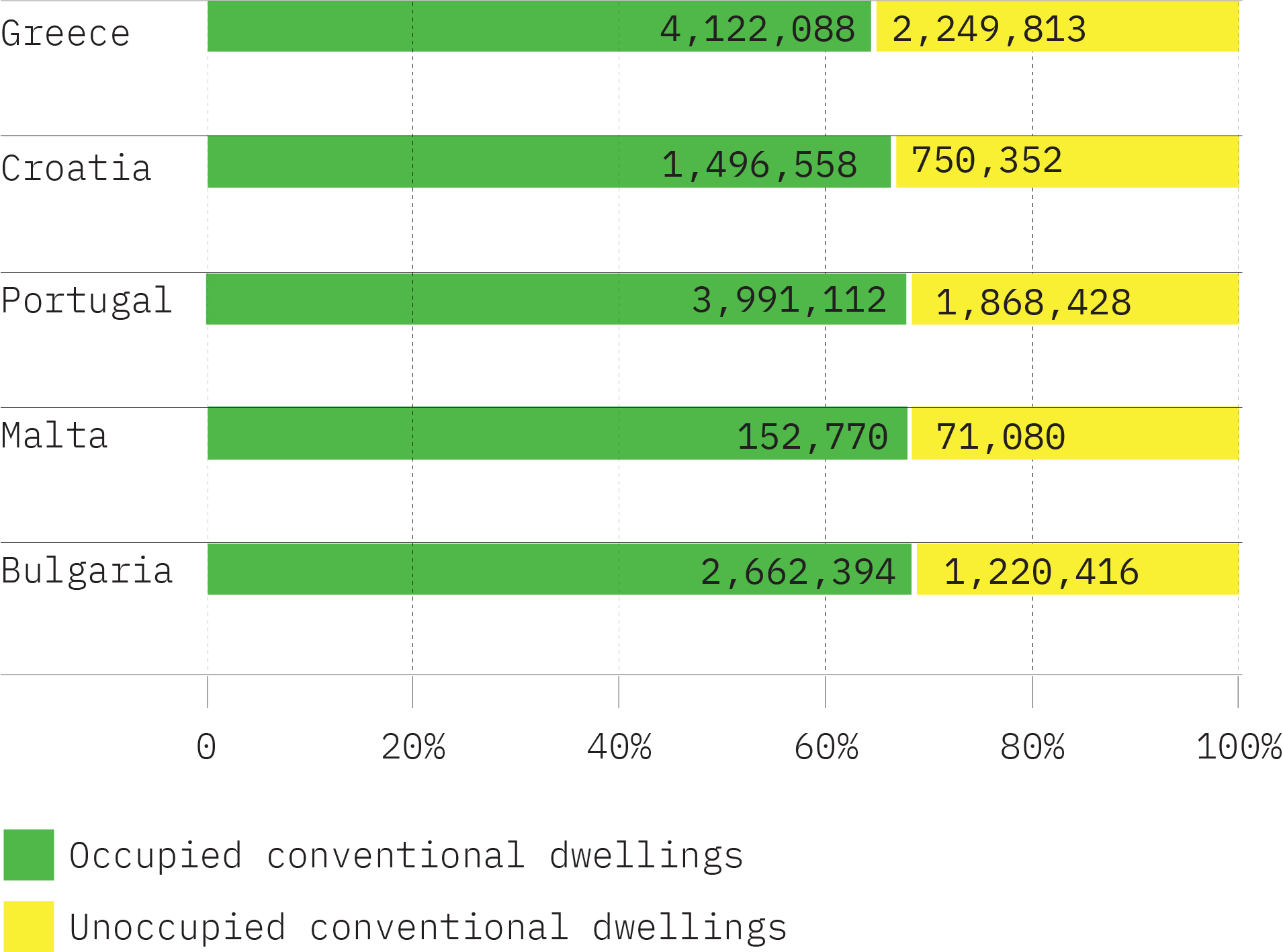

Europe is suffering through an extended period of economic instability. Since the financial crisis, public investment has fallen, particularly within the Euro area countries that were hit by the sovereign debt crisis: Croatia, Portugal, Greece, Spain, Cyprus and Ireland.31

European Central Bank, ‘Public Investment in Europe’, ECB Economic Bulletin, Issue 2, 2016, [link], (accessed 9 July 2019), p. 5. Since 2012, net public investment across the Eurozone has hovered around zero.32

M. C. Klein, ‘Italy Embraces China, and Europe’s Elites Have Only Themselves to Blame’, Barron’s, 5 April 2019, [link], (accessed 15 May 2019). The effect has been growing poverty and inequality, stagnant wages, high unemployment and underemployment, and crumbling infrastructure — particularly in those Eurozone countries subject to the most stringent policies of austerity. Even in wealthy countries like Germany, investment has fallen by a third since the 1970s.33

World Bank, ‘Gross fixed capital formation’, [link], (accessed 19 July 2019).

The situation is markedly different when considering countries that benefited from EU cohesion funds. In Latvia, Poland, Romania and Bulgaria, net public investment increased in the period between 2012 and 2014 compared with 1995 to 2007.34

European Central Bank, 2016), p. 5. Nonetheless, these countries have failed to catch up economically to their western neighbours; few investments have been directed toward raising the living standard of the broader population. And, even in the so-called “cohesion countries”, public investment today is below its long-term average.35

D. Revoltella, P. de Lima and A. Kolev (eds.), ‘Retooling Europe’s Economy – EIB Investment Report 2018/2019’, European Investment Bank, 2018, [link], (accessed 10 July 2019), p. 65.

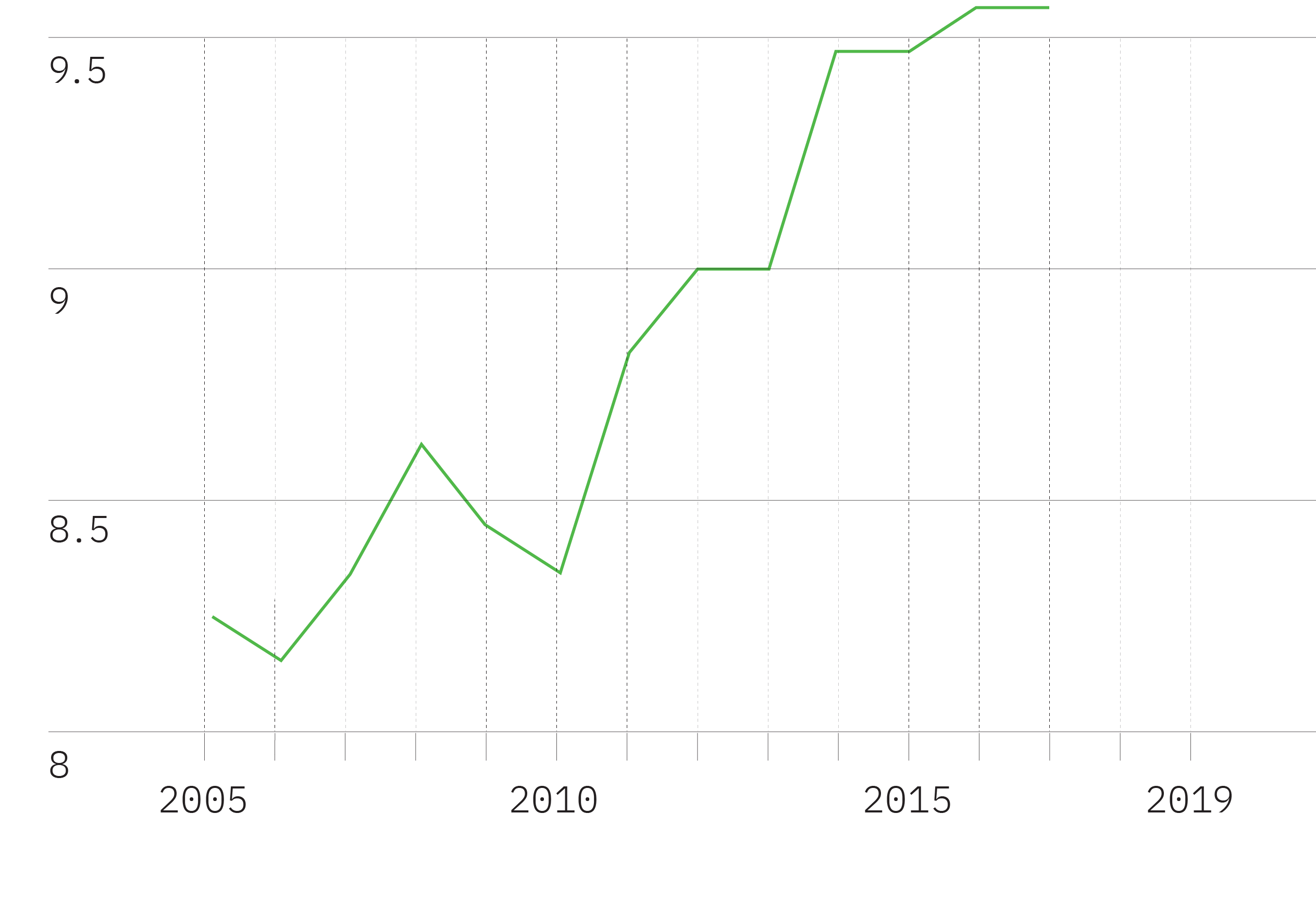

Figure 4

Net public investment across the Eurozone

Investment spending minus depreciation, billions of euros per year.

Source: Eurostat, Barron's

In fact, countries in which net public investment has increased exemplify the challenge facing Europe as a whole. How money is invested matters more than how much: financing cannot support environmental breakdown and social stagnation. For example, cohesion funds have been used to fund multinational corporations moving manufacturing from Western to Eastern Europe to engage in wage arbitrage.36

C. O’Murchu and A. Ward, ‘Questions surround EU relocations’, Financial Times, 1 December 2010, [link], (accessed 29 July 2019). See also, The Bureau, ‘Multinationals cash in on EU fund’, The Bureau of Investigative Journalism, 29 November 2010, [link], (accessed 29 July 2019). These funds contribute to the extraction of wealth from local workers to international firms — and do nothing to boost social outcomes.

Europe has the tools to begin reversing these trends starting today — recalibrating finance to serve society and planet.

Its public banks can marshal the funds necessary to combat climate and environmental breakdown, while breathing new life into Europe’s economies — and reinvigorating the European project.

The means to pay for the GPW exist because the European Central Bank (ECB) is a sovereign currency issuer.37

By its own admission, it cannot go bankrupt. See D. Bunea et al., ‘Profit distribution and loss coverage rules for central banks’, European Central Bank Occasional Paper Series, No. 169, April 2016, [link], (accessed 15 July 2019), p. 14. The severe constraints imposed on government spending across the Eurozone are therefore artificial. The real constraints on government are potential inflation and the availability of real resources.

The Green New Deal for Europe not only makes sense in the context of a stagnating European economy. There is also a clear environmental and social imperative to make it a reality.

Why, then, has it not been implemented?

The dominant mode of economic organisation, based on the primary role of private finance and the gradual privatisation of state services, has weakened European governments and sapped them of vital assets, just as major public investments are required to address the economic and environmental crises. A crucial function of public financing, then, is also to challenge the financial practices on which the politics of austerity were built.

The GPW Financial Strategy

Financial institutions and the infrastructures of financial intermediation have come to play a central role in our lives. This process is sometimes described as ‘financialisation’, which refers to “the increasing role of financial motives, financial markets, financial actors and financial institutions in the operation of the domestic and international economies”.38

G.A. Epstein, ‘Introduction: Financialization and the World Economy’. In G. A. Epstein (Ed.), Financialization and the World Economy, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd., 2005, pp. 3-16.

Through privatisation, deregulation, and credit flows, financialisation has overseen a large-scale conversion of public wealth into private capital. The 2008 financial crisis magnified this process. Around Europe, bank bailouts were financed through the imposition of cuts in public spending.

Reforms to private finance are important, but they are insufficient to respond to the crisis with the urgency it demands. Firstly, there is a growing consensus that the scale of the mobilisation required cannot be met with pricing mechanisms alone — it must be supported by a holistic transformation of our economy.

Secondly, the global financial system is ill-suited to the scale of investment needed for a just transition. It is structured around the pursuit of short-term profit. Compensation and reward packages are based on quarterly or annual reporting and short-term goals. Prudential regulations are short-termist in their outlook and rating agencies rarely look beyond a three-to-five-year horizon.39

European Political Strategy Centre, ’Financing Sustainability – Triggering Investments for the Clean Economy’, EPSC Strategic Notes, Issue 25, 8 June 2017, [link], (accessed 20 June 2019), p. 11. Investments in renewable energy bring returns over much longer timeframes than traditional financial institutions require.

Finally, the private sector is, at best, agnostic to the core principle underpinning every aspect of the Green New Deal for Europe: economic justice. The green transition calls on investments not just in projects that can generate profits for investors, but also in initiatives that produce social returns — enhancing community resilience and wellbeing. The profit motive cannot deliver such outcomes, even with significant prodding.

The effect of a lack of public investment and intervention means that vital investments in renewables remain underfunded, while global finance continues to be a major driver of climate and environmental breakdown around the world. Since 2016, just 33 global banks invested $1.9 trillion in fossil fuel companies.40

‘Banking on Climate Change’, Rainforest Action Network, 2019, [link], (accessed 15 June 2019), p. 9.

The first task of the Green New Deal for Europe, then, is to begin the process of moving away from the unstable and environmentally-destructive model of financialisation, returning finance to its roots: serving local communities through deposit-taking and lending. It recognises the vital role of cooperative banks, farmer-driven financing in agriculture, credit unions and other community-based financing architectures.

And, by massively expanding the role of public finance, it challenges the risky, short-termist, speculative activities of global finance — while reorienting the debate towards the pursuit of public purpose, environmental sustainability and economic justice.

Harnessing Public Investment

When a government decides to build a new hospital, establish a new university or expand a train line, it does so through debt financing. Over time, the investment generates returns: better public health reduces healthcare spending, better-educated people pay more taxes, good public transport ensures cleaner air and lower travel costs.41Opportunity costs drive this logic. Resources are limited, so the fewer resources we use to achieve a given outcome the better. Europe’s green transition must be funded in the same way. Existing central and public investment banks, as well as public procurement procedures, are best-placed to make this happen.

Public investment banks are financial institutions operated by the public: typically, a government agency or company acting with democratic accountability. Public banks have one or more specific mandates — such as supporting small- and medium-size enterprises — that they carry out within a given country or region. Rather than accruing to shareholders or wealthy individuals, the returns from public investments are distributed to the public in the form of improvements to infrastructure, housing, public services or other areas.

Public banks can also operate without a profit-maximisation imperative if given a public mandate to do so. They are better-placed than private banks to identify and protect long-term social assets — the public sector’s rates of return are typically lower than commercial ones, allowing longer investment horizons and less punishing productivity requirements. And they are better equipped than their private counterparts to finance priority economic sectors and geographic regions. In other words, they generate the kinds of social returns that the pursuit of profit alone cannot deliver.

Public procurement procedures under the GPW can be used as a driver for the materials and energy transition, and empowering communities. Whether in infrastructure or housing projects, public procurement should be used to minimise environmental harm and build community wealth. Stimulating demand for green materials and fossil-free energy through public procurement accelerates the transformation of energy-intensive industries while empowering communities.

It is clear that there are sufficient public resources to support a global transition. Research by the Transnational Institute suggests that “public finances amount to more than US $73 trillion, equivalent to 93 percent of global gross domestic product, when we include multi-laterals, pension and sovereign wealth funds, and central banks.”42L. Steinfort and S. Kishimoto, ‘Public Finance for the Future We Want’, The Transnational Institute, 24 June 2019, [link], (accessed 29 July 2019), p. 11.

To ensure not only that Europe’s green transition meets the scale of the challenge, but also that the benefits of the transition accrue to the public, the Green New Deal for Europe calls for a change in institutional priorities, and a substantially enhanced role for public sector investment and asset ownership.

First, all EU will shift away from a focus on Gross Domestic Product to a Genuine Progress Indicator. This requires a new Directive to set out what may and may not count as ‘genuine progress’ in economic performance. GDP measures of ‘growth’ include the pollution of our environment, damage to our climate, sales of unsafe food or products, or practices that damage labour and social rights — so long as they have contractual value. Instead, the EU needs to adopt a measure of sustainable human and environmental well-being.

Second, the ECB’s mandate will be clarified to focus on ‘full employment and social progress, and a high level of protection and improvement of the quality of the environment’ as the Treaty on European Union requires.43Treaty on European Union article 3(3) This will be made clear in a new EU Regulation to complement but ultimately override the ‘price stability’ target.44Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union article 282 Price stability must itself be clarified to preclude escalating wage or income inequality, and escalating housing costs. This will refocus European monetary policy on what truly matters.

Third, the European Investment Bank (EIB), as the world’s largest multilateral public bank, is best placed to raise the necessary funding for the GPW. But it will need a radically new approach to do so. The EIB’s existing financing programmes have significant shortcomings. Under the European Fund for Strategic Investments (EFSI), for example, investment is based on a model of public-private partnerships that seeks to “nudge” private financiers into making longer-term, higher-risk investments — the dominant model for public investment today.

Rather than absorbing the investment risks themselves, private investors expect public banks to invest with them — providing public guarantees for private loans. The effect is that the risks are socialised — any losses are paid for by the public — and the gains are privatised.45 T. Marois, ‘How Public Banks Can Help Finance a Green and Just Energy Transformation’, The Transnational Institute, 15 November 2017, [link], (accessed 20 June 2019). This deprives the state of capital needed to make further investments in the economy.

In a special report, the European Court of Auditors affirmed the weaknesses of the public-private financing model — emphasising that it generates outsized profits for private financiers. “The risk allocation between public and private partners was often inappropriate, incoherent and ineffective, while high remuneration rates (up to 14 %) on the private partner’s risk capital did not always reflect the risks borne.”46O. Herics et al, ‘Public Private Partnerships in the EU: Widespread shortcomings and limited benefits’, European Court of Auditors Special Report, No. 09, 2018, [link], (accessed 10 November 2019).

Current financing programmes also lack grounding in democratic processes. Under EFSI, just eight experts ultimately decide whether to back projects with a public guarantee.47‘European Fund for Strategic Investments’, [link], (accessed 10 July 2019). This creates a significant disconnect between the needs of communities and the resources that are made available to them.

Finally, the GPW will do away with this model of public-private partnership and focus on investing directly in Europe’s green transition in a way that is democratic and participatory. To ensure that sufficient funding is raised and properly allocated, the EIB must adopt a multi-stakeholder model, uniting climate experts, labour unions, policy makers, EU member state representatives, NGOs and economic actors — including representatives of energy cooperatives — to ensure that its strategy is long-term, democratic and immune from capture.

2 Policy Recommendation: Switch to a Genuine Progress Indicator system of accounting rather than Gross Domestic Product across all EU institutions.

3 Policy Recommendation: Enact a new Regulation clarifying that the European Central Bank must prioritise employment, social progress and environmental protection.

4 Policy Recommendation: Move away from the model of public-private financing and ensure that the benefits of public investment remain in public hands.

5 Policy Recommendation: Adopt a multi-stakeholder governance model for the EIB.

Green Investment Bonds

When governments raise money through debt, they issue bonds. A bond is a financial instrument that represents a loan made by an investors to a borrower — a sovereign government, municipality or corporation can issue and sell bonds to a range of investors (bondholders). A green bond is a financial instrument that is issued specifically for making green investments. The EIB was among the first to issue green bonds in 2007 and is now the world’s largest issuer of such instruments.

Raising funding for the GPW through green bonds has two key advantages. First, the current European rules restricting spending and deficits will not apply, allowing for a significant expansion of public finances without breaching Europe’s fiscal compact. Second, no new European taxes will be necessary. This will avoid the need for renegotiating Europe’s treaties.

The bonds issued by public investment banks will be purchased by private investors on the secondary markets. To ensure that these bonds do not lose their value, the ECB would announce its readiness to purchase them if their yields rise above a certain level. By guaranteeing to buy all green bonds on the secondary market, the ECB would eliminate the risk of insolvency for the green bonds.

The removal of default risk will, in turn, provide a stable and risk-free investment. It will also ensure that speculators will not be able to financially attack the Green New Deal for Europe, while shielding the programme from attempts by the market to “discipline” public spending.

In this sense, EIB-issued green bonds are a win-win for Europe. Pension funds in countries like Germany, hungry for safe assets, can use them to secure a safe return on investment. Under EU prudential regulations, banks investing in sovereign debt (bonds issued by governments) or public bank-issued loans do not have to hold any capital for their investment, so there are strong regulatory incentives to buy them. On the other side of the continent, countries like Greece will be able to benefit from decent jobs and high-performing infrastructure, ending its crises of unemployment and underinvestment.

6 Policy Recommendation: Fund the green transition by mobilising a coalition of Europe’s public banks — led by the European Investment Bank — to issue green bonds to raise at least five percent of Europe’s GDP in funding that can be channelled into the GPW.

Macroprudential Management

Finance faces two key risks from the climate and environmental crises.

On one hand, the transition to a net-zero-carbon economy will pose a significant threat to returns on fossil fuel investments and could trigger a rapid sell-off.48

P. Monnin, ‘Central banks should reflect climate risks in monetary policy operations’, SUERF Policy Note, Issue No 41. Citigroup estimates that global exposures to fossil fuels amount to $100 trillion.49

Jason Channel et al., ‘Energy Darwinism II: Why a Low Carbon Future Doesn’t Have to Cost the Earth’, Citigroup, 2015. If banks fail to divest themselves of these assets, a sudden collapse in their prices could trigger a systemwide shock.50

New Economics Foundation, ‘Central banks, climate change and the transition to a low carbon economy: A policy briefing’, 2017, [link], (accessed 25 July 2019).

This would devastate communities that depend on these industries: a fire-sale of non-renewable assets would lead to large-scale job losses and send shockwaves through industries that still depend on fossil fuels.

On the other, climate and environmental breakdown pose risks for physical assets.51

G.D. Rudebusch, ‘Economic letter: Climate change and the federal reserve’, Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, 2019, [link], (accessed 1 August 2019). As weather patterns become more extreme, increasing damage to real estate, infrastructure, crops and other assets will become a financial stability risk in itself. Europe’s central banks must be prepared to address these risks at the multilateral and global level.

Within Europe, the European System of Central Banks (ESCB) must establish multilateral technical working groups on the green transition, enabling coordinated action by Europe’s central banks to mitigate physical and transition risks and coordinate the purchase of green bonds issued by Europe’s public investment banks.

In particular, to anticipate the market chaos that could result from a collapse in prices for non-renewables, the ESCB must prepare to support the orderly winding down of Europe’s fossil fuel companies. Only a holistic approach that tackles fossil fuel workers, infrastructure and ensures the environmental clean-up of polluted sites will ensure a just, stable transition. Indeed, this is the ambition of the Green New Deal for Europe. Central banking policy must play a key role in managing the financial stability risks arising from the reorientation of Europe’s economy to support this transition.52

Some proposals go further. For example, The Next System proposed a public-buyout of all fossil fuel companies. It argues that this would not only lay the groundwork for a just transition for fossil fuel workers — it would also avert a probable systemic shock to global financial markets. If priced correctly, based on an accounting of fossil fuel companies’ long term prospects and role in climate breakdown, the buyout can take place at a highly discounted rate. See C. Skandier, ‘Quantitative Easing for the Planet’, The Next System Project, [link], (accessed 24 July 2019).

And, as Europe introduces new prudential standards (see section 4.3.4 below) and other regulations to address climate and environmental risks, the ECB should also play a key role in reshaping the global narrative on prudential standards, ensuring that the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) and its Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) put climate and environment front and centre in future iterations of global macroprudential standards.

Policy Recommendation: Establish multilateral working groups on the green transition within the ESCB to coordinate the green bond purchasing programme and to control for physical and investment risks.

Policy Recommendation: Intervene in the design of global prudential standards to introduce punitive capital requirements for investments in fossil fuel-heavy and environmentally-destructive projects and businesses in the Basel framework.

Taxation and the GPW

The core financing mechanism of the GPW programme — issuing green bonds to power the green transition — does not preclude raising taxes to assist in it.

On the contrary, taxation plays a vital role in the Green New Deal for Europe, not only as a means of raising funds, but also a vehicle for achieving environmental and social justice.

For decades, European legislators have overseen the construction of an international financial system that permits widespread tax evasion both within the EU and just outside its borders.53

For a clear illustration of these efforts, see “Luxleaks,” a set of leaked documents revealing the Luxembourg government’s sweetheart deals with multinational corporations to get their taxes down to zero. Working communities, meanwhile, have continued to pay their fair share, even when the returns to their tax payments — in services, in infrastructure — have declined.

Over the same period, European legislators have presided over a massive system of subsidies for environmentally disastrous industries, damaging communities within their own constituencies and also outside of them.54

ODI, ‘Phase-out 2020: monitoring Europe’s fossil fuel subsidies’, September 2017. Rather than restrained, polluting corporations have been let loose on the world.

A radical overhaul of the tax system is, therefore, doubly necessary: first, to demand that those who profited from environmental destruction help to finance our response to it; second, to curtail the system of incentives that allowed them to do so in the first place. Such an overhaul is outlined in greater detail in the Environmental Union (EnU) proposal that follows.

However, given the scale of the crisis at hand — and the political roadblocks that are endemic to tax legislation — taxation is simply not a substitute for direct and immediate public financing. And public balance sheets are more appropriate in managing transition risks than private households or private sector. Green bonds, therefore, remain the essential ingredient of the GPW programme.

How to Spend It

Once raised by the EIB, the funds from the sale of green investment bonds will be funnelled into the GPW. There, through a budgeting process that balances participation and climate expertise, the money will be allocated to a series of transnational, national, regional, municipal and local projects, creating new space for communities to direct essential investments towards social and environmental justice.

Guaranteeing Decent Jobs

Proponents of ‘full employment’ in the post-war era often proposed a trade-off between job creation and environmental protection. They promised to drive equitable industrial growth — but only at the expense of ecological balance.

This promise is now broken, leaving us with the worst of both worlds: economic growth that delivers a declining share of wealth for labour and increasing destruction of the environment.

For more than a decade now, the international trade union movement has been advocating for a ‘just transition’ to a post-carbon economy — one that responds to the crisis of employment insecurity and reinvests in the infrastructure that has been left to crumble.

The GPW answers these social demands. Building on years of painstaking collective work in ‘climate jobs’ campaigns across Europe, the GPW aims to guarantee decent work to all those who seek it, centred on living labour — the people who will make the transition — and managed by workers, working-class communities and the organisations that represent them.

In the process, the GPW undermines the argument that environmental action is at odds with the interests of labour. The GPW ensures that workers and communities in Europe will benefit both in terms of health and the stability of their environment, and in job opportunities and income. And it will ensure that the jobs created in Europe will not be supported through environmental devastation elsewhere. In this sense, the GPW is part of a global climate justice agenda.

But the GPW will go beyond a simple job guarantee. The reduction in material throughput required by the Green New Deal for Europe will create slack in certain labour markets, particularly in fossil fuel-dependent industries. To avoid worsening unemployment and exacerbating poverty, the GPW will act as a driver for lower working hours and better pay (see also section 3.4.6 below).

The EU can therefore lead the transition to a three-day weekend or other reduction in working time while ensuring that workers’ wages increase, by fulfilling the commitments of EU member states in the European Social Charter 1961.55European Social Charter 1961 section 2(1) requiring reduction of the working week in accordance with ‘increase in productivity and other relevant factors’. The Working Time Directive will be updated to increase paid holidays for workers, so that people can have the flexibility and security to choose the right balance of work and life.56Working Time Directive 2003/88/EC articles 5 and 7 hold current weekly rest and annual leave rights.

Figure 5

Increasing share of EU working poor

Percentage of working people at risk of poverty.

Source: Eurostat, @valentinaromei, FT

To advance the cause of economic democracy, however, higher wages and better working conditions are not enough. The GPW will ensure that workers have a voice at the level of office, firm, and industry. A new Economic Democracy Directive can guarantee that workers will have the right to be represented on the boards of companies, have a minimum share of voting power in firm meetings, and have representation in all capital savings, pensions or worker funds. This will be mandatory for all jobs created under the umbrella of the GPW.

As a public project, the GPW will not be constrained by short-term investor demands. This will create new possibilities for people to earn a living outside the sphere of capital accumulation. And, because work provided through the GPW involves production for use rather than exchange, it can be channelled toward environmentally sustainable projects and methods of production that will not and cannot be undertaken by the private sector. Workers under a job guarantee can earn a dignified living doing anything that is publicly deemed to be of social value, including caring for the elderly, children and people who are ill or disabled; habitat restoration; and community services.

For example, under Roosevelt’s New Deal, the Civilian Conservation Corps was both a jobs plan and an environmental project: its goal was to plant hundreds of millions of trees across the US to restore topsoil in the wake of the Dust Bowl. Similarly, the GPW could put people across Europe to work on restoring local environments that have been degraded — supporting the restoration of Europe’s natural habitats.

By focusing on local and municipal investment, the GPW creates local job opportunities. This can help reduce levels of involuntary internal and international displacement of people — while reducing the related challenges of housing and pressure on social and health services.

The GPW will, in particular, emphasise the need for creating new green jobs in rural communities: green and cottage industries, nature preservation, rewilding, organic farming, forestry and forest products, and other regenerative activities. Greater prosperity in rural communities will reverse the wealth drain that these regions continue to see, with businesses and investment moving back, increasing community resilience and reducing the need for commutes.

The GPW also commits to investing in programmes of re-training so that people can deploy the skills acquired working in carbon-intensive jobs (i.e., engineering, project management, and others) in the sustainable conversion of the economy. It will provide an income guarantee for every worker from a fossil fuel employer, excluding directors or senior managers, that must be phased out by law, so that people will maintain their living standards.

Finally, the GPW will recognise that reproductive and care work represents a significant amount of time allocated for personal, household and community wellbeing and the protection of and struggle for human rights which is integral to care work. The GPW, then, includes provision for a Care Income (CI) — based on the recognition of the necessity of the activities of caring, which are often undervalued or invisible in our societies and overwhelmingly performed by women — especially mothers. This can be made available to people who are not formally employed, but are engaged on a full- or part-time basis in care — parents caring for their children, children caring for their elderly parents, and community members caring for each other and the environment.

By providing social and financial recognition, the CI would provide an incentive for people to engage seriously with care work. This, in turn, would provide security for disabled people — facilitating access to the care they need to live independently. It would also help remedy the structural disadvantages faced by women and other caregivers in today’s economy — overcoming the scourge of unequal pay.

Finally, the CI would strengthen families. In parts of Europe, children are being taken into care at an alarming rate.57The Association of Directors of Children’s Services Ltd, ‘A Country that Works for All Children’, ADCS Position Paper, October 2017, [link]. This is the result of policies such as austerity which have impoverished families, particularly single-mother families, and the privatisation of children’s services, which have added a profit motive to removing children. A Care Income would redirect resources towards mothers and children, supporting social services in enabling families to stay together.